For the Winter Olympic Games in Milan-Cortina 2026, Getty Images launched an ambitious creative project with three of its photographers: Pauline Ballet, Ryan Pierse and Hector Vivas. Thermal cameras, infrared, multiple exposures, and even a 1956 Graflex camera… far from traditional sports coverage, the agency explores new ways of photographing sport. Pauline Ballet, who covers ice sports in Milan, looks back on this experience.

Getty Images at the 2026 Winter Olympics: between editorial work and creative innovation

As the IOC’s official photographic agency, Getty Images naturally covers all events at the Milan-Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic Games. But alongside this editorial work, the agency set up a separate creative project, entrusted to three photographers: French photographer Pauline Ballet, Australian Ryan Pierse and Mexican Hector Vivas.

The idea: to offer a different perspective on winter sports, stepping away from traditional coverage to explore unprecedented techniques and visual approaches. The project is divided into several series.

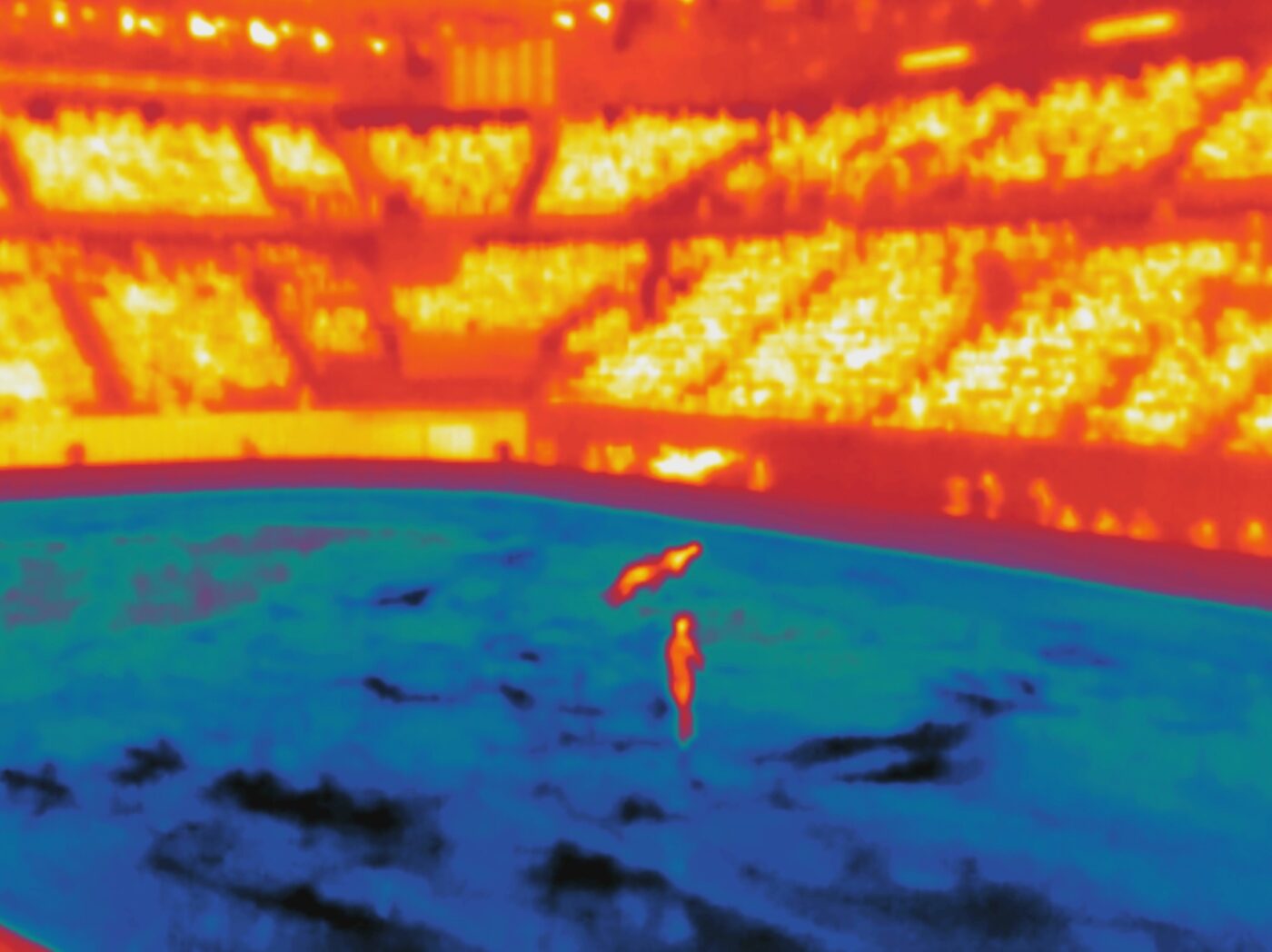

- Winter Heat uses thermal cameras to reveal athletes’ body heat on the ice – bodies appear in warm tones against blue and indigo backgrounds,

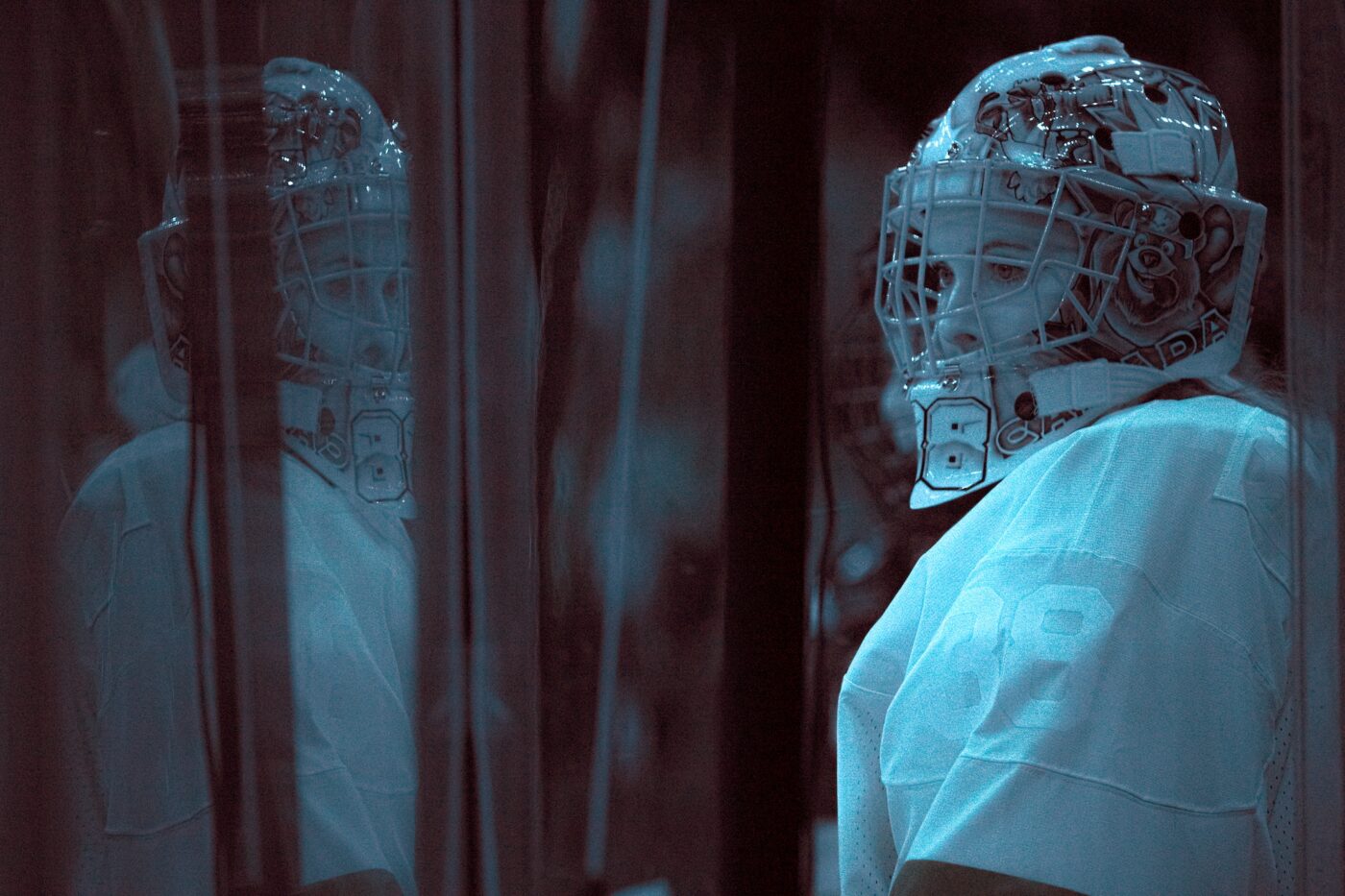

- Infrared relies on modified camera bodies to capture the spectrum invisible to the naked eye,

- Back to the Future pays tribute to the 1956 Cortina Olympics by using period Graflex cameras,

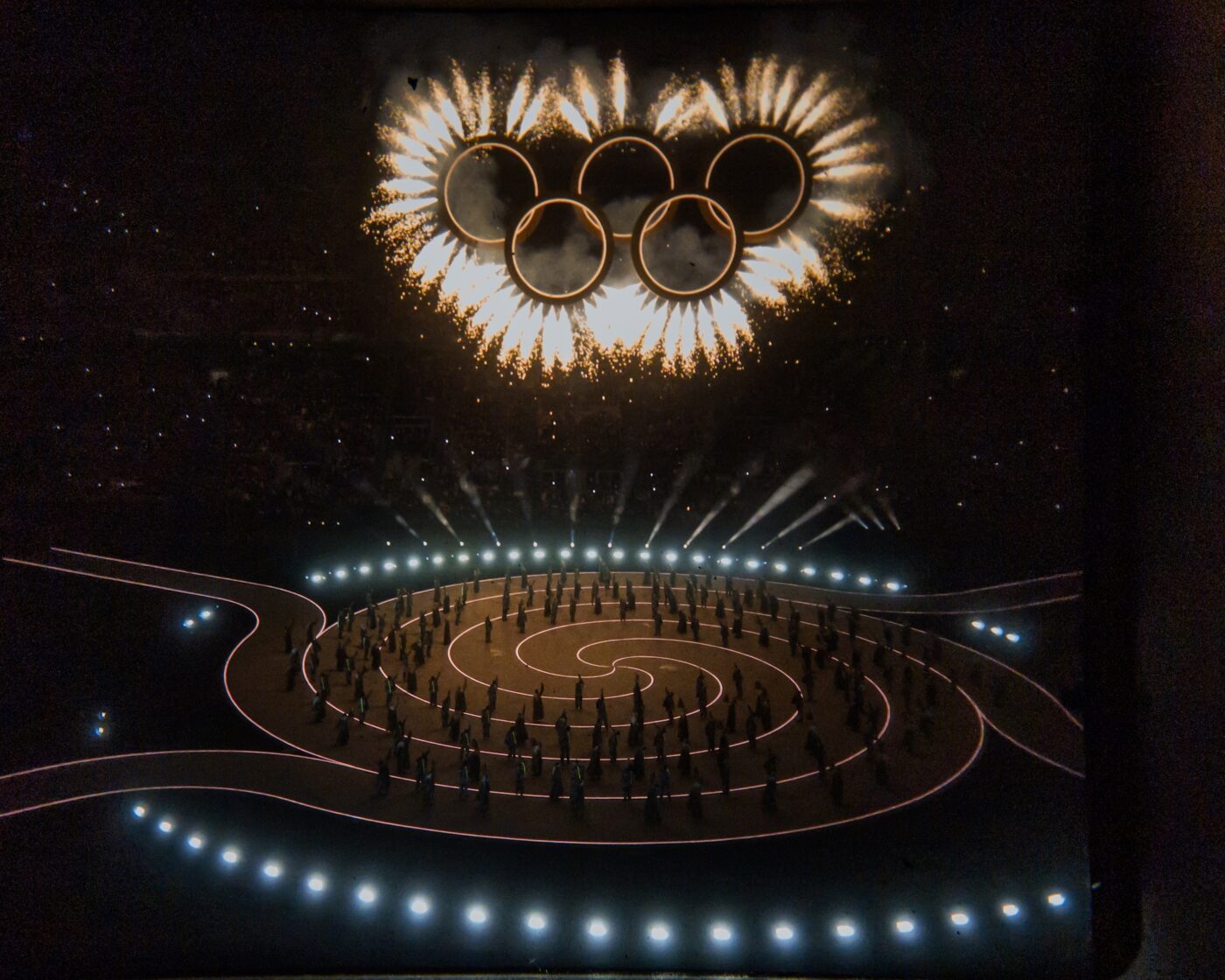

- Olympic Projections projects images from the Games onto Milanese architecture,

- Layers of the Game overlays multiple shots taken from a fixed point to capture the full course of an event in a single image.

It was as part of this project that we spoke with Pauline Ballet, based in Milan to cover ice sports.

After the excitement of Paris 2024, how do you approach a Winter Games, where weather conditions and light are radically different?

Pauline Ballet: I was super curious and enthusiastic. I always find it exciting to go photograph new sports, with the stress building up. It’s inevitable and actually a good sign, because it pushes you to surpass yourself. For my part, I’m based in Milan and I photograph ice sports.

I was quite apprehensive about the switch to artificial lighting, especially since we were using, as part of a creative project with Getty Images, new tools such as infrared, thermal imaging, and even a Graflex (a model equivalent to the one used at the 1956 Cortina Olympics, Ed.). I knew I was going to lose several stops of light and that the colors wouldn’t render as well as outdoors. That was indeed the case, but these limitations and constraints pushed me to seek out other textures, angles, and to develop very creative ideas.

How did you tame the thermal camera, which isn’t designed for sports photography? What does body heat reveal beyond a simple action shot on the ice?

Pauline Ballet: We use thermal cameras, repurposing them from their industrial or scientific use to turn them into a true photographic tool. There are clear technical constraints, particularly the inability to choose our usual photographic settings, such as shutter speed, aperture, or focal length. There is also a delay between pressing the shutter and the actual image capture, which is really disconcerting at first.

But it also pushes us to reinvent composition, since our visual references change completely. Being able to capture the infrared radiation emitted by bodies, rather than visible light, allows us to elevate the muscular effort and the thermal exchanges between the athlete and the environment they perform in. It is both a documentary tool and a poetic medium, which questions the notion of performance by revealing the thermal intensity of the athlete’s effort under specific conditions.

Also, working with the infrared spectrum completely changes the way snowy or icy landscapes are read. Is it a deliberate choice to transform the Olympic venue into an almost surreal world?

Pauline Ballet: Yes, there is in any case a desire to move away from the classic documentary image and take it toward other visual worlds. The contrasts of infrared transform snowy landscapes into lunar or almost extraterrestrial deserts. We’re in a world between sport and science fiction. It reinforces our approach of trying to reveal what the eye cannot perceive and to look at sport differently.

Overlaying numerous athletes requires significant upstream work and post-production. What motivated such an approach?

Pauline Ballet: This is truly the project that takes us the most time, without a doubt. I spent hours training on Photoshop before the Games, and I’ve also spent a few late nights on it here. Upstream, there’s scouting time to find an interesting angle and the spot where we can safely set up the camera. It’s essential that the camera doesn’t move at all, in order to make the retouching work easier afterwards.

Then, in post-production, meticulous and precise retouching work is required, athlete by athlete. But I think it’s worth it: these composites allow us to go beyond the single moment and tell the story of the movement, the event in its duration, and the collective energy.

Similarly, using a vintage Graflex in Cortina, 70 years after the 1956 Games, is a powerful historical nod. What relationship with time does it impose, knowing that modern sport is a race toward immediacy?

Pauline Ballet: What a magnificent object this Graflex is – I find it wonderful. The contrast between the slowness of the process and the speed of modern arenas is staggering. For sports photography, I think it’s the most demanding camera, with its manual focus. It’s a reminder that each image can be a deliberate choice and not just a burst. But there are a huge number of missed shots before you can produce a satisfying image.

It’s also quite funny to take portraits of spectators who immediately pose, while it takes me at least a minute to manually focus, which creates rather suspended moments.

You worked on these series with Ryan Pierse and Hector Vivas. How does the vision of three photographers come together on a shared project? Is there a form of collective “art direction”?

Pauline Ballet: It’s extremely enriching – without a doubt the most stimulating project I’ve ever worked on. The initiative was born from ideas shared upstream by Getty Images’ sports content direction, with Paul Gilham and Matthias Hangst, in dialogue with their photographers.

Then, all three of us – with Ryan and Hector – shared our inspirations, references, and knowledge, with this idea of showing the invisible, before letting our individual creativity express itself in the field. They are very inspiring photographers, and it’s wonderful to be able to share a common passion. Each of us experiments on our own events, and every day we debrief on what works more or less well.

The sidelines have long been a male-dominated space. How have you seen the role of women sports photographers evolve in recent years? Do you feel there is a different sensitivity or approach in the way physical effort is documented?

Pauline Ballet: The female presence is increasingly visible, especially at major events, and that’s genuinely great news. I remember the photographers’ meeting before the Tour de France, 10 years ago, where there were maybe three women, compared to dozens and dozens of male photographers… There’s still work to be done, but I feel like I’m meeting more and more independent women photographers and that agencies have this awareness and desire for equality.

Regarding the approach, I couldn’t identify what the differences would be. For me, it’s more a matter of individual perspective and sensibilities, rather than gender.

What advice would you give to a young photographer who wants to join an agency or cover events on the scale of the Olympics?

Pauline Ballet: To get out in the field as much as possible, to show your work, to build your own personal visual language rather than trying to fit a mold. To stay confident and to arm yourself with perseverance and patience.

Ultimately, what is the sporting event you’ve most enjoyed covering?

Pauline Ballet: It’s the first time I’ve covered ice sports and I love it. I’ve never been bored and I look forward to going out and shooting every day. Each sport has something I enjoy – the most impressive is short track speed skating, but I think my favorite photos are the ones from figure skating.

What is your standard gear for covering a high-level competition?

Pauline Ballet: Normally for a sports competition I work with two Nikon Z9 camera bodies, with the Nikkor Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S, Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S, Z 70-200mm f/2.8 VR S and a Z 400mm f/2.8 TC VR S. Plus a flash, batteries and a multitude of accessories.

With the evolution of technology (mirrorless cameras, predictive AF, extreme burst rates), do you feel your profession has changed? Does it free your mind for composition, or does it complicate image culling?

Pauline Ballet: The evolution of cameras and sensors is reassuring in a way, and I’m even more aware of it after spending two weeks photographing with a Graflex… Today, we can capture images or freeze moments that were once impossible, like a tennis ball deforming the strings at the moment of impact. Autofocus tracking is also impressive, particularly with Nikon’s 3D tracking, which allows for much more flexible composition.

But all of this remains technical, and the ideal is probably to manage to forget about it quickly. On the other hand, for those with a heavy trigger finger, you can easily end up at the end of the day with thousands of images to cull… and hard drives already full.

For sport and especially the Olympics, speed is crucial. Can you describe your live production workflow? How do you manage editing while continuing to shoot the action unfolding in front of you?

Pauline Ballet: It’s clearly a mental juggling act: shooting, editing, transmitting… it can all happen almost simultaneously. For these Games and the creative project carried out with my team, I edit the images myself at the end of each competition I photograph. During the actual shooting, I’m therefore entirely focused on the image, simply making sure to tag my favorite photos to speed up the initial selection. And that’s really an ideal condition for producing work.

I then move on to post-production, before uploading and captioning the images on the agency’s website. In an editorial context, however, you have to photograph and send the images to editors very quickly in real time, which requires being attentive to the moments when that becomes possible.

Beyond the camera body and lenses, what is the essential (and perhaps unexpected) accessory you bring to these Winter Games?

Pauline Ballet: A water bottle, prisms/filters, my AirPods, cereal bars.

As the Games draw to a close, what is the image you haven’t yet managed to capture and would love to get at all costs?

Pauline Ballet: Tonight (Wednesday, February 18, Ed.), I’m going to photograph short track speed skating. Since the start of the competition, I’ve had this image in mind: an athlete’s hand brushing the ice with their fingertips during the race… I hope I’ll manage to capture it then.

Thank you to Pauline Ballet for answering our questions, as well as to the Getty Images teams for organizing this interview. You can find Pauline Ballet’s work on Instagram, her website or on the Getty Images platform.