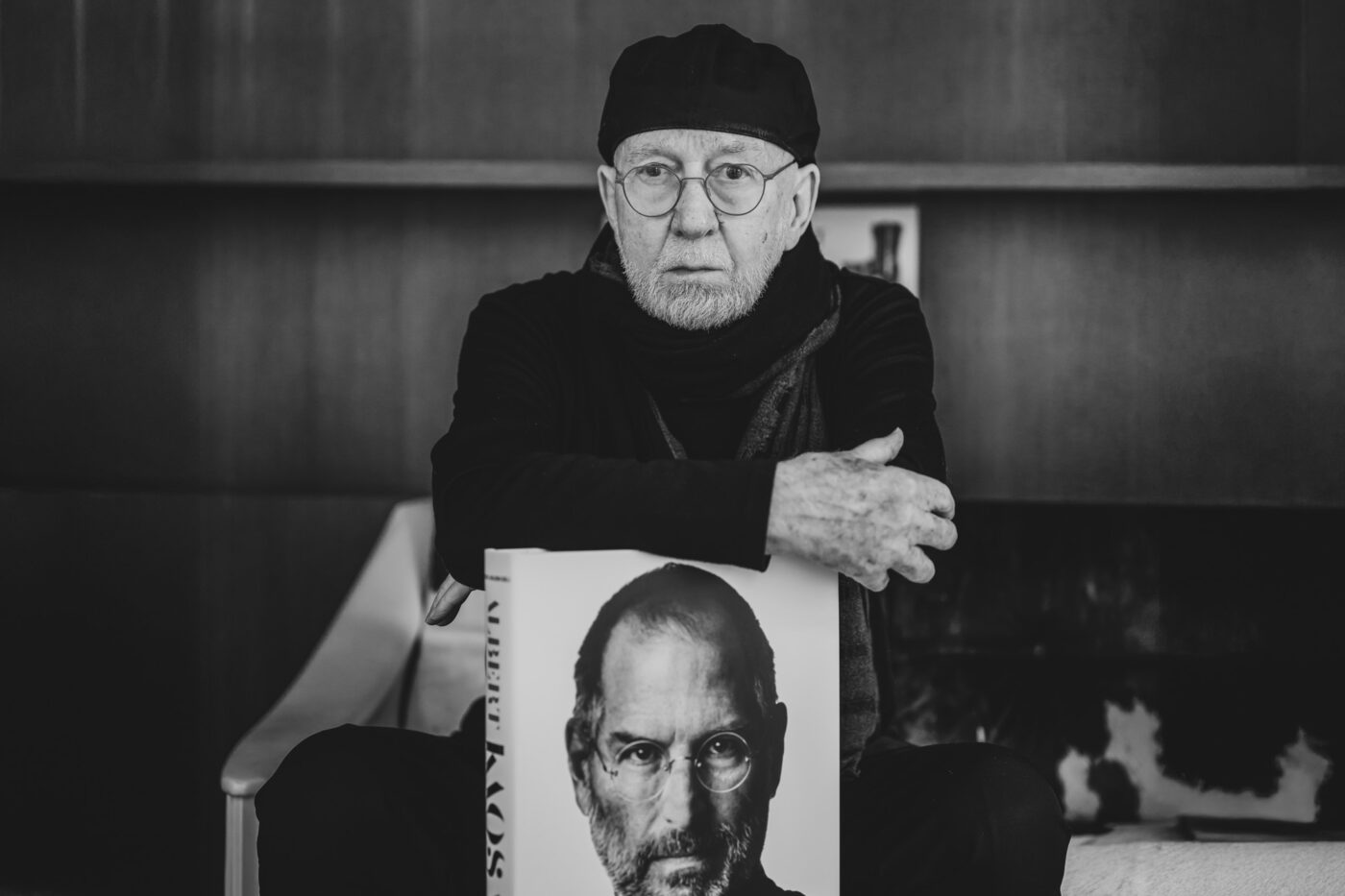

On the occasion of Paris Photo 2025 and the reissue of his book Kaos in XL format by Taschen, we met with Albert Watson. Between anecdotes about his iconic portraits of Steve Jobs and Hitchcock, reflections on AI, and advice for young photographers, he shares his vision of an exceptional career.

84 years old, more than 180 magazine covers, iconic portraits of Steve Jobs, Alfred Hitchcock, and Jack Nicholson. In the setting of the Taschen gallery at 2 rue de Buci in Paris, Albert Watson welcomes us to talk about Kaos, his major work, which is being reissued in a new edition. The man has lost none of his verve. An unfiltered conversation with one of the most influential photographers of our time.

Sommaire

- Kaos, new edition

- Seven years of training that shaped everything

- Steve Jobs: the art of absolute simplicity

- Hitchcock and the goose: the turning point

- The importance of simplicity: magazine covers

- An undiminished passion for all subjects

- The power of the gaze

- The technical question: from 35 mm to digital medium format

- AI: primitive but interesting

- Advice for young photographers: passion above all else

Kaos, new edition

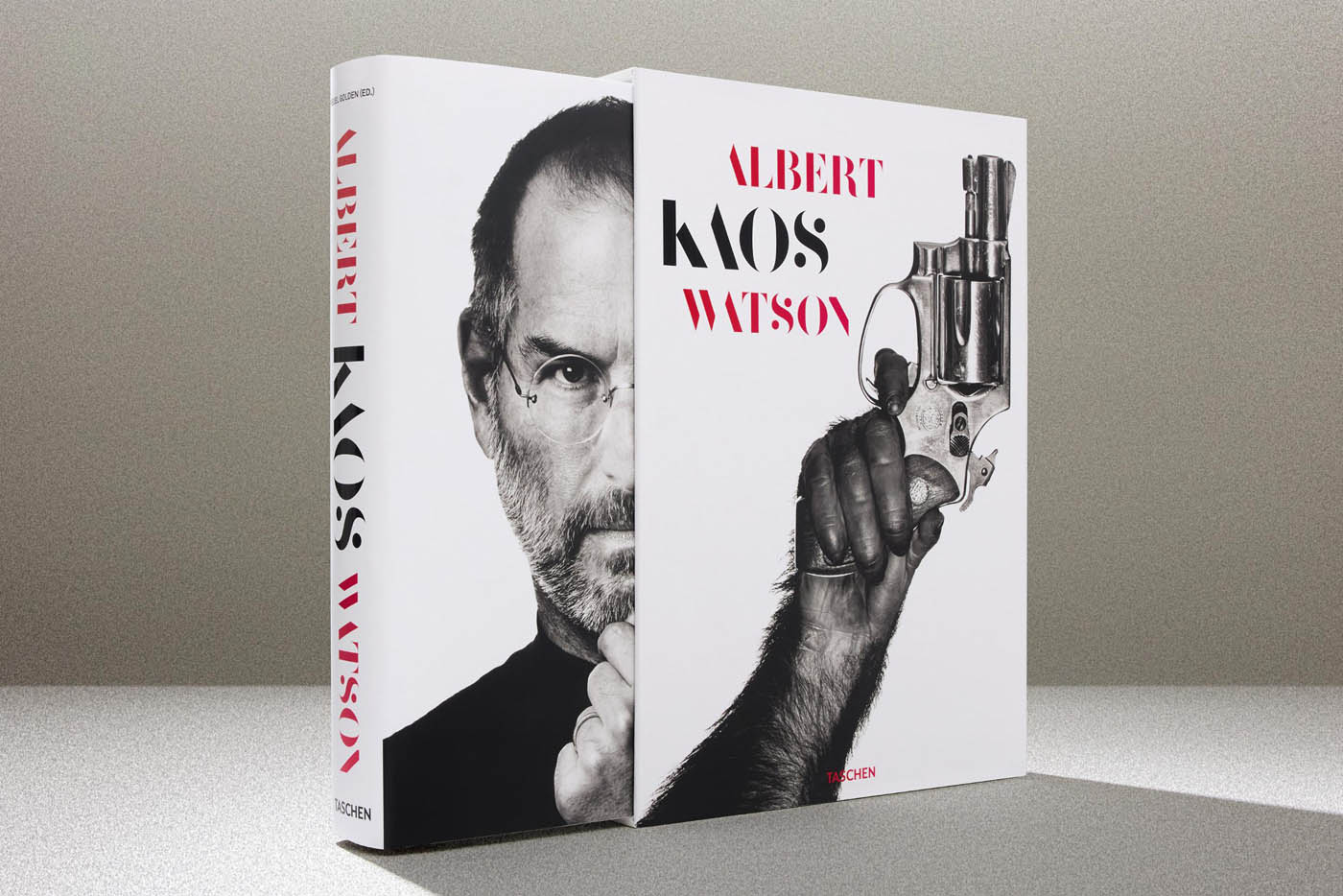

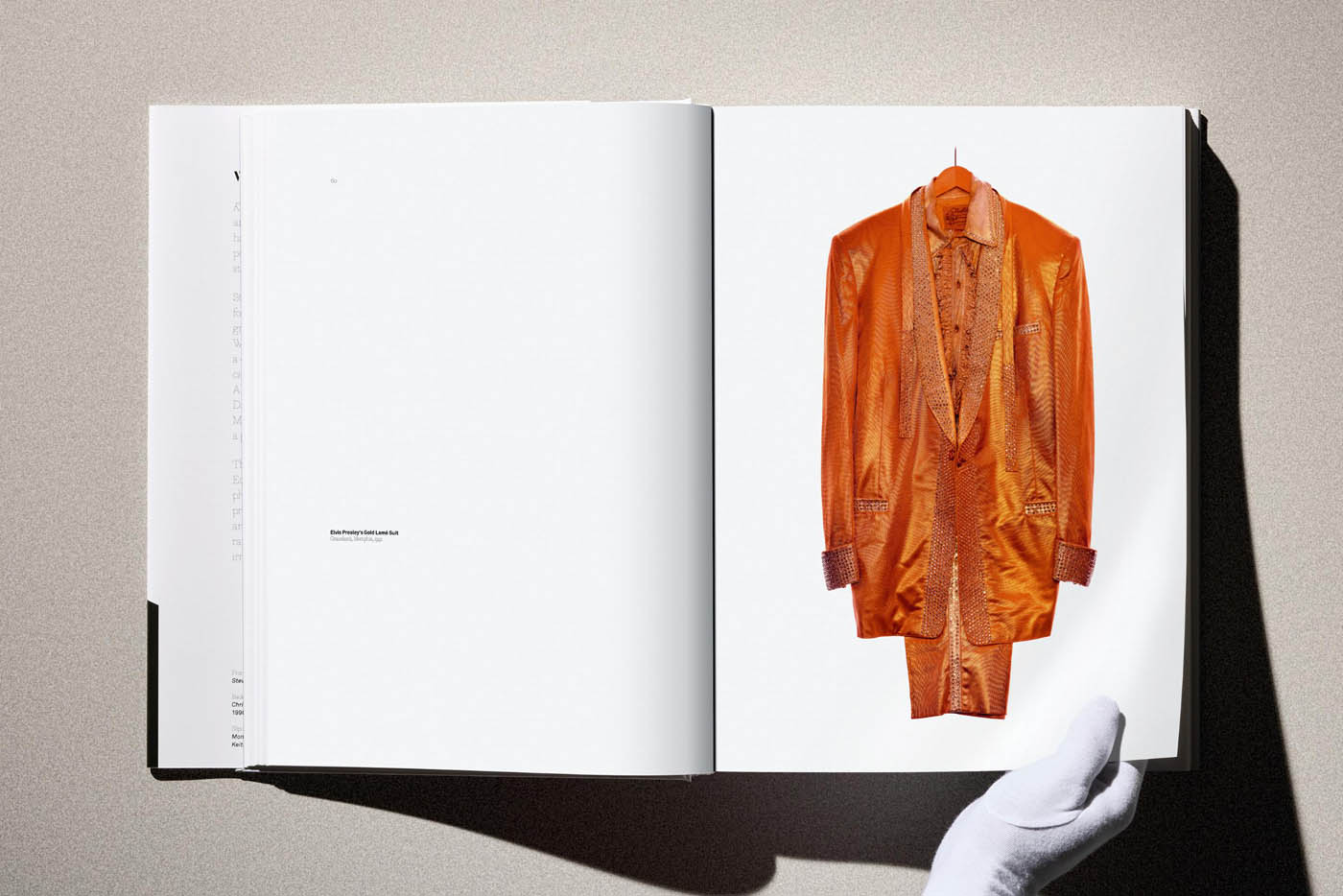

Albert Watson traveled to Paris for the reissue of Kaos by Taschen. This new version includes a few adjustments compared to the original. “There is only one photograph that is different in this new version,” he explains. “It comes from the Rome project that I just finished. I had a major exhibition in Rome at the Palazzo Esposizioni Roma.”

The other change? The removal of R. Kelly’s portrait, with a pragmatic explanation from Watson: “Since he went to prison, the publisher preferred to remove it from the publication.” An editorial decision that reflects the sensitivity of the time to ethical issues.

Seven years of training that shaped everything

Contrary to what one might think, Albert Watson did not follow a linear path from graphic design to film and then photography. “I spent seven years at art school, earning a traditional degree, a master’s, and a doctorate. It was a long time; I was about 27 or 28 when I finished,” he explains. It was during his second year that he discovered photography, as part of his graphic design studies at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in Dundee, Scotland.

One teacher in particular would have a profound impact on his career. “I was very lucky to have a teacher who was himself an excellent photographer and extremely passionate about his work. But above all, he was obsessed with printing. He firmly believed in the importance of putting work on paper, on a wall.”

This demand for print quality has stayed with Albert Watson to this day. “Even with digital, I keep all the printing work in-house. I never outsource it. All the prints you can buy come from our gallery, from our studio.” It’s a philosophy inherited from those formative years.

This multidisciplinary training is evident in every image in his book Kaos. “If you look at Kaos, you’ll see that graphic design is really everywhere. Some images are purely graphic. But others combine graphic design with a cinematic approach—particularly with the use of tungsten lighting.”

Some images are purely graphic. But others combine graphics with a cinematic approach.

Albert Watson

Steve Jobs: the art of absolute simplicity

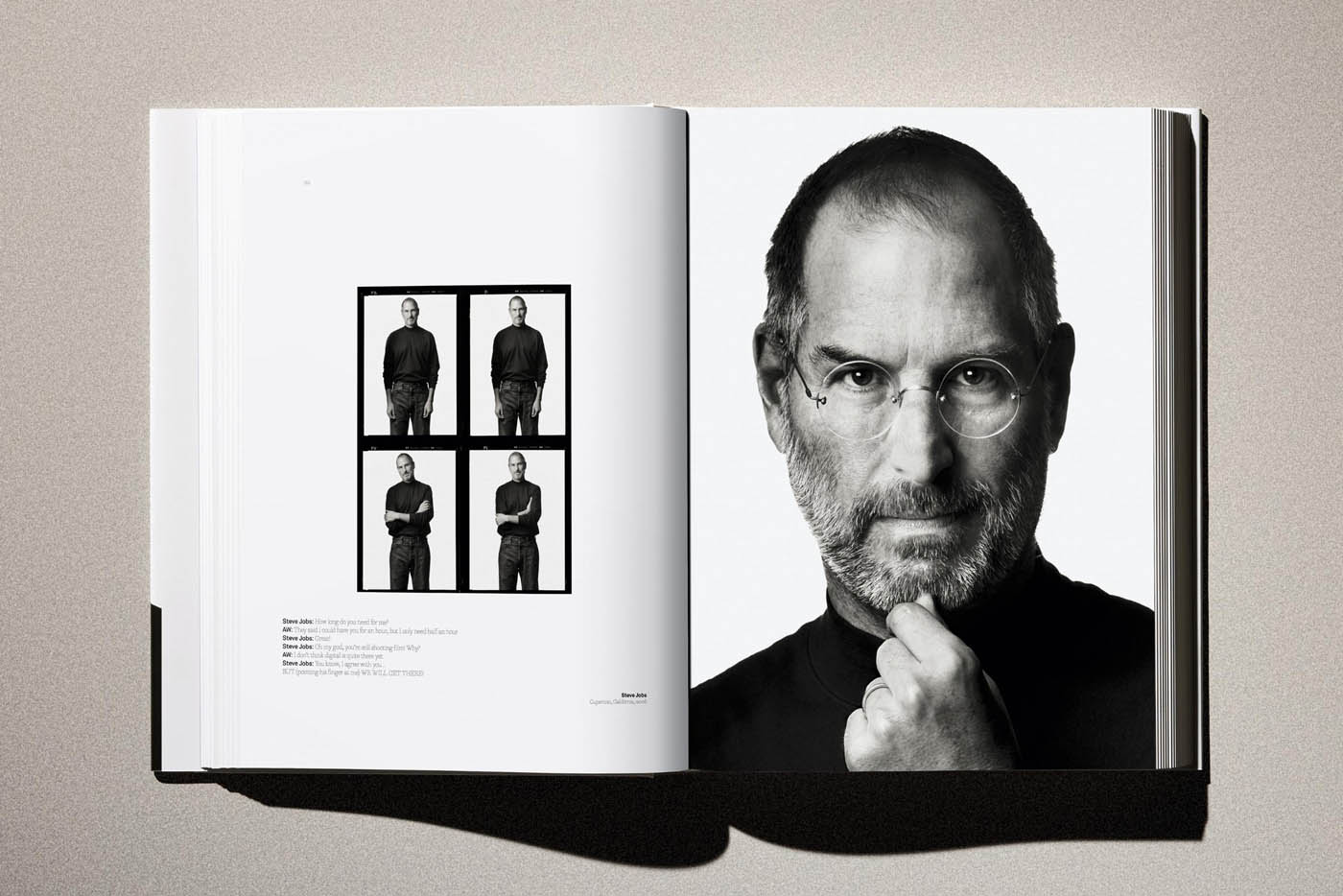

One of Albert Watson’s most iconic images is his portrait of Steve Jobs. It’s a photograph that perfectly illustrates his philosophy of minimalism. “I knew that with Apple, this portrait had to be really simple,” he tells us.

Albert Watson draws a parallel with Apple Stores: “You walk in, and if you didn’t know Apple, you wouldn’t be entirely sure what they sell.” This empty space, this minimalism, had to be reflected in the portrait. There was no question of photographing Steve Jobs in his office; that would have resulted in a reportage. Albert Watson wanted something iconic.

To get the perfect expression, he imagined a specific scenario: “I said to him, ‘Imagine you walk into your office, on one side of the table. On the other side, there are people who work for Apple, but they don’t like your ideas. You’re the boss.'” Steve Jobs’ response was immediate: “No problem, that happens to me every day.”

Albert Watson continues: “I asked him to think about smiling—or rather NOT smiling, but to think about listening. To think: I’m listening to what you’re saying, but I know I’m right. And he said: that’s easy for me.” The result is that icy stare, with that slight, restrained smile. “And when he saw the photo, he loved it.”

Albert Watson sums up the essence of this portrait: “The image is almost like a passport photo, you know. But better. What you feel is this attitude: ‘I’m listening, but we’re going to do it my way.’ That’s exactly the feeling that comes across, someone who is strong and confident.”

Hitchcock and the goose: the turning point

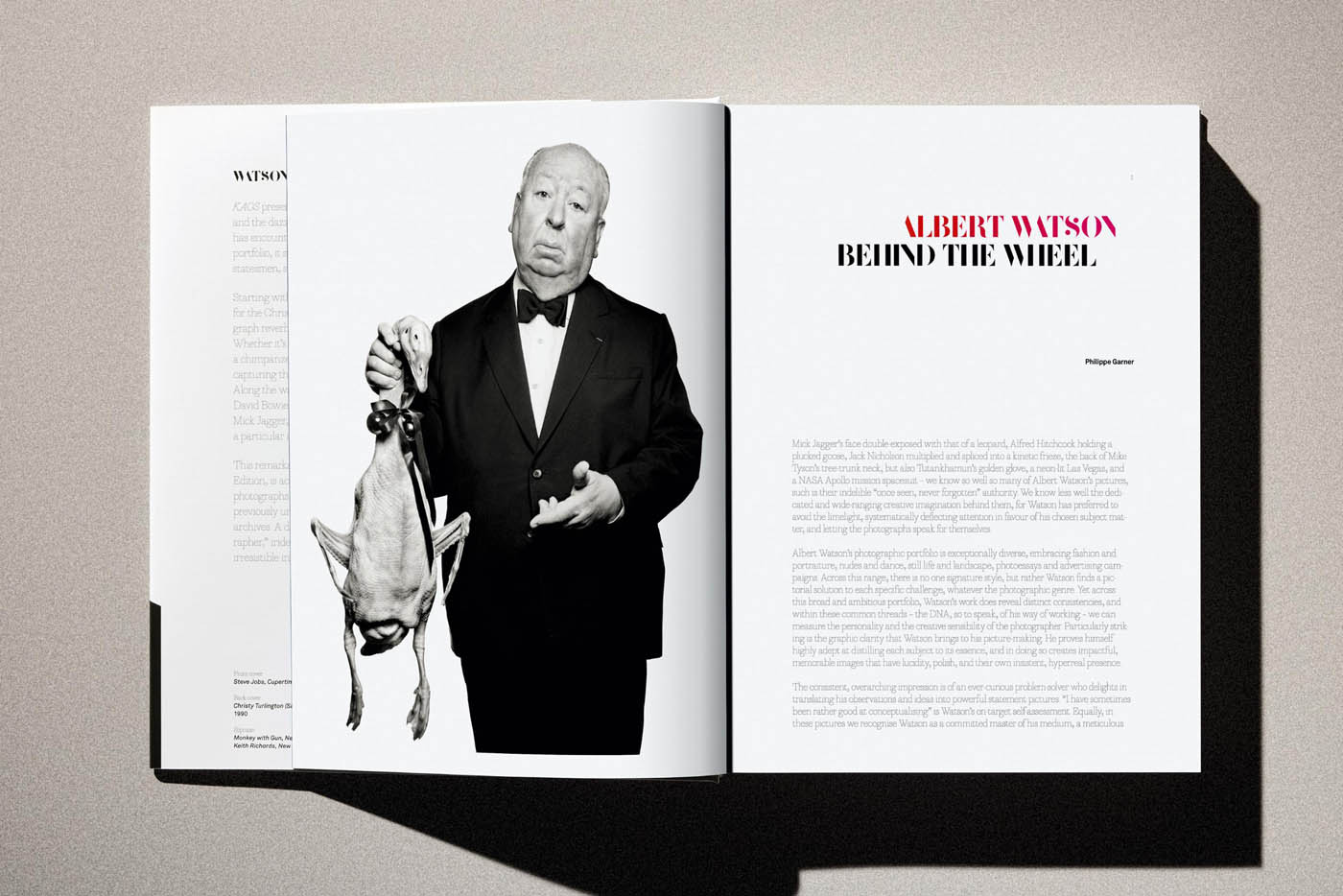

Another iconic image marks the photographer’s career: Alfred Hitchcock holding a plucked goose, photographed in 1973 in Los Angeles. Originally, Harper’s Bazaar magazine wanted to photograph the director holding a plate with the goose on it for a Christmas recipe article. Albert Watson, fresh out of film school, dared to suggest an alternative.

It was a very important image for me, mainly for reasons of trust.

Albert Watson

“Very politely, I said, ‘Sure, I can photograph the goose on a plate, but it makes me feel like Hitchcock would look like a maître d’hôtel. I thought we needed something more Hitchcockian.'” His proposal: use a plucked goose with its head still attached, held by the neck. “It looks like he killed it himself.” “

This image was a turning point, but not for the reasons you might think. “It was a very important image for me, mainly because of confidence. I was nervous about taking this photo because it was Alfred Hitchcock. I had just graduated from film school, so I was a little scared to have Hitchcock in front of me. But I took a deep breath and said to myself: either it will be a success or it won’t. And of course, it was a success.”

Albert Watson humbly admits, “I’ve always cited this image as one of my favorites, not because it’s the best. I think there are better images. But with Hitchcock and the goose, it’s just very iconic and memorable. People remember it more than other images.”

The importance of simplicity: magazine covers

How does a photographer manage to produce more than 180 magazine covers during his career? Albert Watson reveals his secret: “When you look at some of the shop windows in New York, they display 20 magazine covers at a time. I realized early on that if I used a certain technique, because of the way I shot, my photo would immediately stand out among all those magazines.”

He explains: “It’s like a visual code. If you see one of my covers, you can spot it from across the street in a second. That kind of instant recognition was the key to success. I’m surprised more photographers didn’t understand that.”

But the photographer is clear-headed about how the profession has changed. “The era of great fashion photography has almost disappeared. It’s very rare today to see real fashion images in the sense that I understood them. The photographers who made their mark in this field, Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, Irving Penn, [Richard] Avedon, these days, it’s over. You no longer see that weight, that gravity in the images.”

If you see one of my covers, you can spot it from across the street in a second.

Albert Watson

An undiminished passion for all subjects

How can such diversity in work be explained over the course of a career? Albert Watson responds with disarming simplicity: “When I started photography, and this is still the case today, I was amazed—and that amazement continues. The simple fact of being able to put a sheet of white paper in a developing bath and see a photograph appear… I was fascinated by this miracle. “

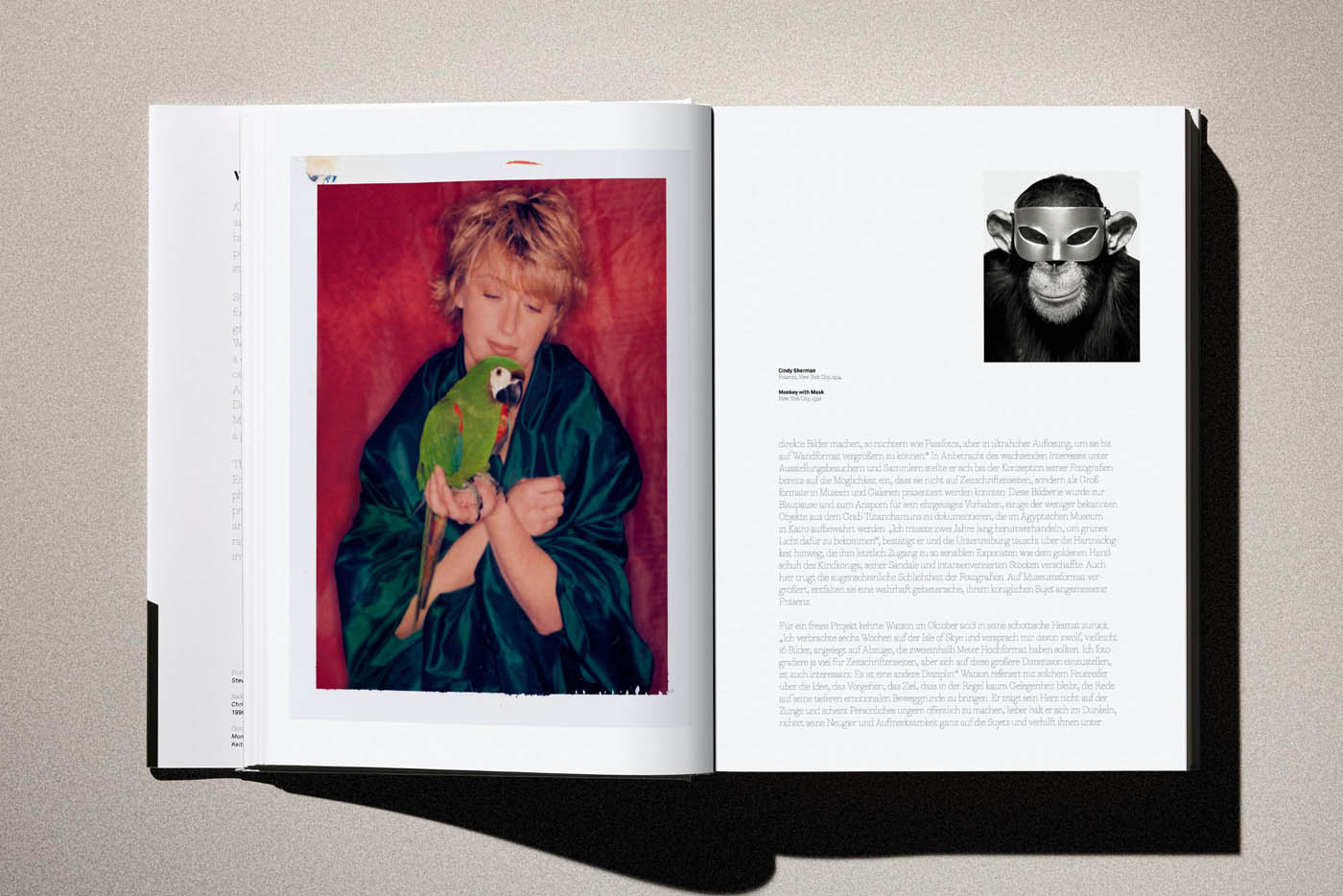

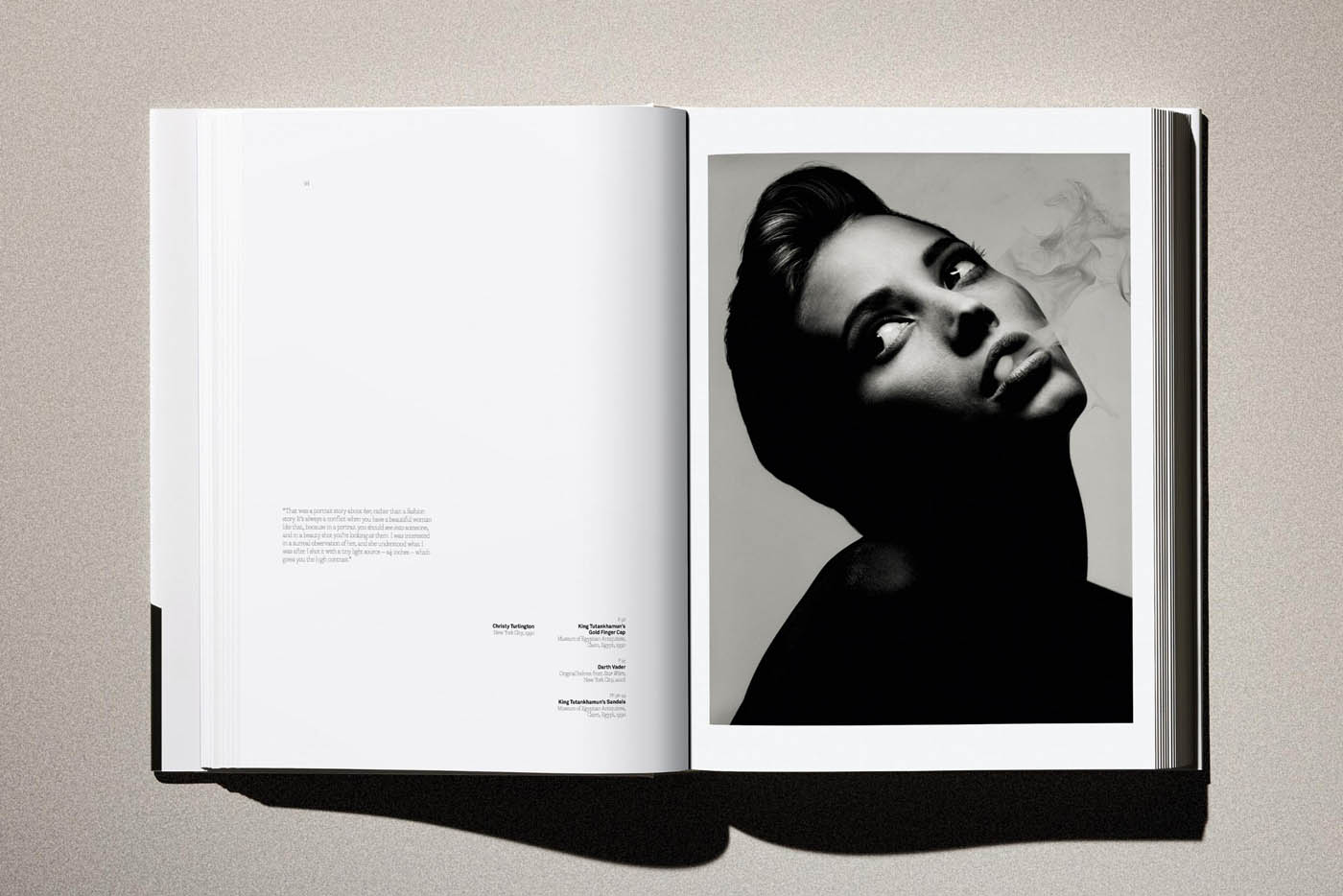

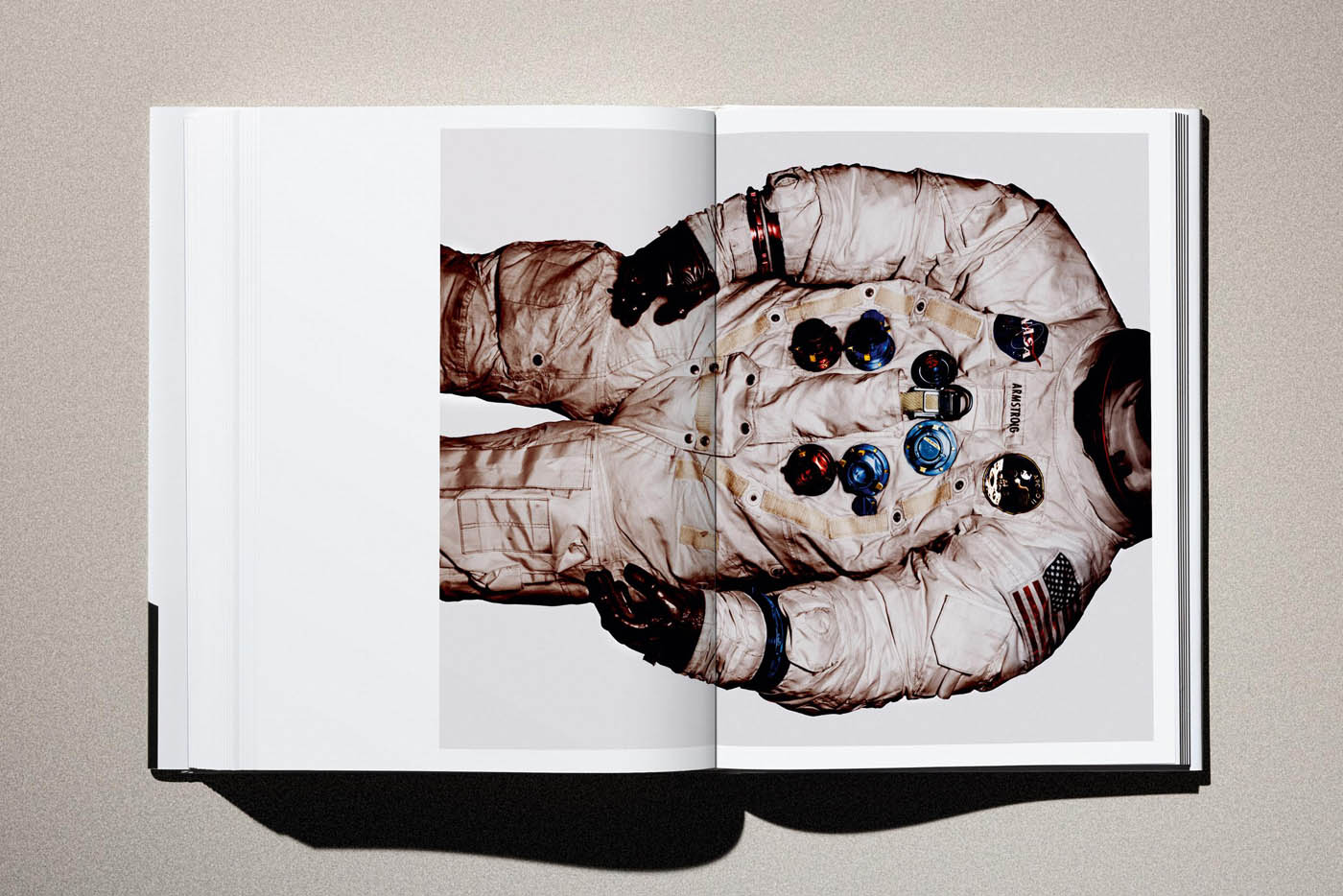

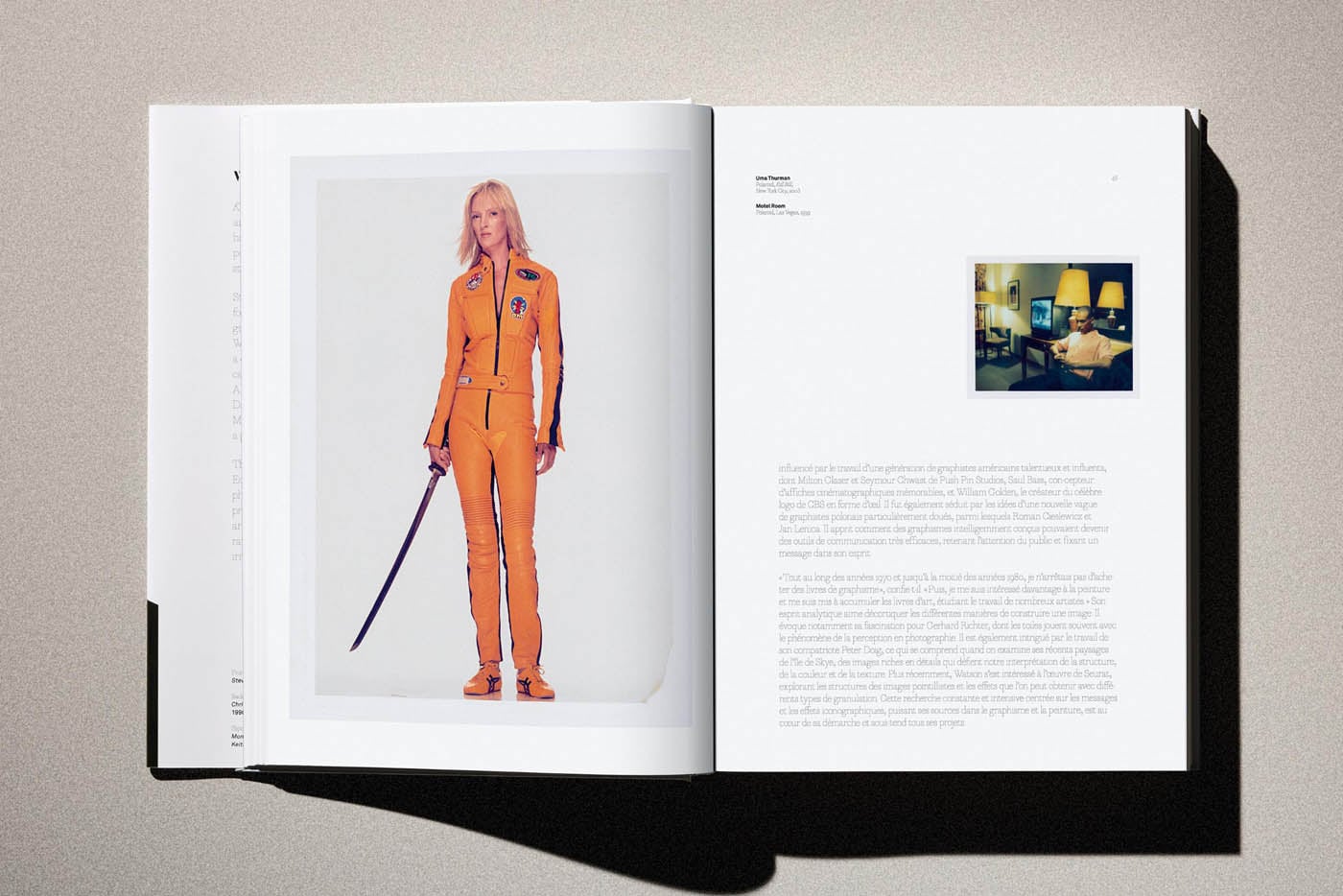

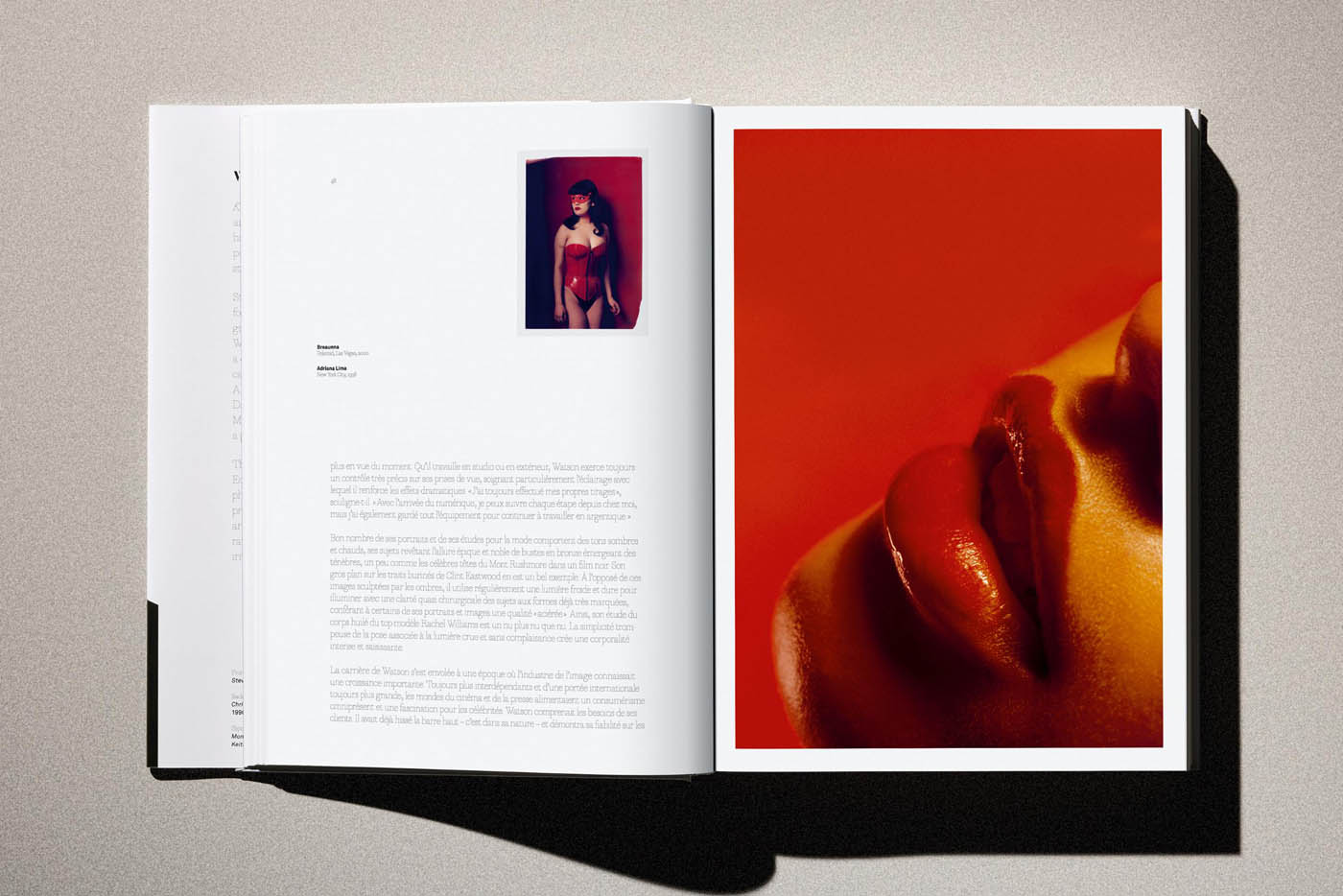

This passion allows him to move from one subject to another with the same enthusiasm: “Take my training in graphic design, my sensitivity to cinema, mix it all together with this passion, and you get someone who can go from fashion photography to photographing space suits, Tutankhamun’s gloves, Elvis Presley’s favorite rifle, a portrait of Steve Jobs or Alfred Hitchcock or Jack Nicholson. I loved every project.”

What is Albert Watson’s style? “I would say it’s a combination of three things: graphic design, a cinematic approach, and passion.”

When I started photography, I was amazed—and I still am today.

Albert Watson

The power of the gaze

In Albert Watson’s portraits, one thing immediately strikes you: the subject’s gaze that draws you in. And the photographer explains: “It’s no coincidence. One of the things we do in galleries is place the portraits at a specific height. Instead of looking up, you are at the same level as the person. Your eyes are at the same height as their eyes. That way, when you look at the photo, the person is looking at you too.”

The goal is clear: “We try to create an image where the photo draws you in, absorbs you. There are several ways to do this. It can be monumental, iconic, super simple, or simply based on direct eye contact. But that’s not always the case. I’ve taken many pictures without eye contact. I like to vary my approach.”

The technical question: from 35 mm to digital medium format

When asked which photographic equipment has been most important in his career, Albert Watson refuses to choose. “It’s difficult to give a short answer,” he admits. For him, the key lies in the constant movement between formats.

He describes a classic progression: “You start with a portable 35mm camera, then move on to medium format, such as a Hasselblad. Next, you move on to a 4×5 camera, then perhaps an 8×10.” Richard Avedon, he recalls, eventually adopted the 8×10 as his format of choice. Albert Watson, on the other hand, found his balance elsewhere: “When I switched from Hasselblad to 4×5, I really liked that format. It suited my style. The 8×10 was too slow, too heavy, too difficult to handle in the field.”

But it is when talking about optics that Albert becomes truly passionate. He refers to what he calls an “optical stretch” specific to large formats: “The way light travels through a large format lens is different from a smaller Canon or Nikon lens. ” It’s a physical quality that’s impossible to reproduce: “You can take exactly the same picture with a 35mm camera, but it’s not the same thing.”

The way light travels through a large format lens is different from a smaller Canon or Nikon lens. You can take exactly the same picture at 35mm, but it’s not the same thing.

Albert Watson

This line of thinking naturally leads him to smartphones. “That’s why your iPhone looks different. The lens is very close to the sensor—just a few millimeters.” He doesn’t disparage this tool: “It’s a device really designed for amateurs, but it makes them better photographers. Suddenly, you take a picture of a sunset with your iPhone and it actually looks like a sunset, instead of being a washed-out mess.”

The photographer also mentions high-resolution medium format cameras. “I discovered that a Phase One camera produces 150-megapixel images, which is equivalent to a medium format camera, but the information is superior to an 8×10 negative. I really liked that.” For his Rome project, he worked with between 150 and 290 megapixels.

He illustrates this capability with a striking anecdote, evoking an image assembled from several 8×10 plates: “There may be a car in a landscape, very small. But you have the ability, in the software, to zoom in and read the license plate.” The information exists, even if no print can reproduce it in its entirety.

Albert Watson also mentions the limitations of technology: “You can create 800-megapixel images by superimposing images, but the problem is that they don’t translate well to print. The printer doesn’t have that capability.”

Albert Watson concludes with a surprising admission: “The technical side of photography was extremely difficult for me. It’s not something I particularly enjoy. Technical aspects bore me.” ” However, he recognizes the importance of mastering these skills: “The more I understood the technique, the more it opened up creative doors. If you want to be a real photographer, you have to learn the technical truth, even if it’s not your passion.”

Smartphones are devices designed for amateurs, but they make them better photographers.

Albert Watson

AI: primitive but interesting

On the subject of artificial intelligence in photography, Albert Watson takes a nuanced position. His initial observation is unequivocal: “The problem with AI is that it doesn’t have enough quality. You create an image using AI, it appears on the screen, you say ‘let’s print it at this size,’ and you think to yourself: it looks awful.”

However, he experimented with AI during his Rome project—and found something unexpected. He uses a linguistic metaphor to explain this phenomenon: “Sometimes, I felt like I was typing in English on the computer and it was responding in French. I would give it ‘one, two, three, four’ and it would send me back ‘un, deux, trois, quatre’. It’s the same thing, but different.” In some images of Roman monuments, the trees in the background came back “with a different accent, a different communication.”

Albert Watson sees paradoxical creative potential in this: “In a way, the primitiveness of AI compared to the human mind… its interpretation of my image, the way it came back to me with a different accent, I found that interesting.” But his conclusion remains measured: “It’s not sophisticated enough. ” According to him, this opens up avenues for reflection for curious photographers.

Advice for young photographers: passion above all else

What advice would you give to someone who wants to become a photographer today? Albert Watson responds with an interesting analogy: “You get into a car for the first time and someone tells you what to do. You start the engine, you look in the rearview mirror. You have to put your foot on the clutch to change gears. Be careful not to hit a pedestrian. Watch out for red lights. When you start, you say: it’s impossible, I can’t do this.”

He continues: “30 years later. You get in a car and drive somewhere, and you can have a phone conversation at the same time. You don’t kill anyone. You respect red lights, you change gears, you reverse, you park. Everything becomes fluid. It’s the same with a camera. To learn how to use a camera, you have to work at it. You have to love it.”

To learn how to use a device, you have to work at it. You have to love it.

Albert Watson

“If you’re interested in fashion photography, you may be attracted by glamour, beautiful women, and beautiful clothes. But what you need to do if you really want to do fashion photography is learn about fashion. You need to study fabrics. You need to know the difference between silk and brushed cotton. It’s important. You need to be passionate about what you’re photographing. “

Albert Watson illustrates his point: “If I’m photographing Steve Jobs, I’m passionate about Steve Jobs. If I’m photographing Tutankhamun’s gloves in the basement of the Cairo Museum, then I have to be enthusiastic and interested. What I have in front of me is the oldest glove in human history, Tutankhamun’s glove.”

He warns: “I think it’s passion that counts. You have to be sure of that. Unfortunately, I’ve had several assistants who were attracted to photography for the wrong reasons. And then they tried to make the leap from assistant to image creator. They couldn’t do it.”

Albert Watson concludes with a chilling statistic: “I’ve had 600 assistants over the course of my career. Only one has managed to become a good photographer. Just one. I’ve had many very good ones, even fantastic ones. But only one has made the leap.”

Thank you to Albert Watson for answering our questions, and to the Taschen gallery for making this meeting possible. You can find Albert Watson’s latest book, Kaos, at the Taschen store.