Every second, more than 61,000 images are taken around the globe, contributing to a visual heritage that is literally exploding. Between selfies, memories shared on social networks and digital archives, the planet now produces over two trillion photos a year. Dive into the dizzying figures of a silent revolution, where each trigger shapes the memory of the XXIᵉ century.

Sommaire

- Exponential production: 2,100,000,000,000 shots by 2025

- Smartphones ultra-dominant, cameras marginalized

- Who takes these photos, and where?

- Personal and social uses dominate

- A colossal (but invisible) visual heritage: 30 trillion images by 2030

- Methodology and reliability: an aggregate of cross-referenced sources

- Conclusion

Exponential production: 2,100,000,000,000 shots by 2025

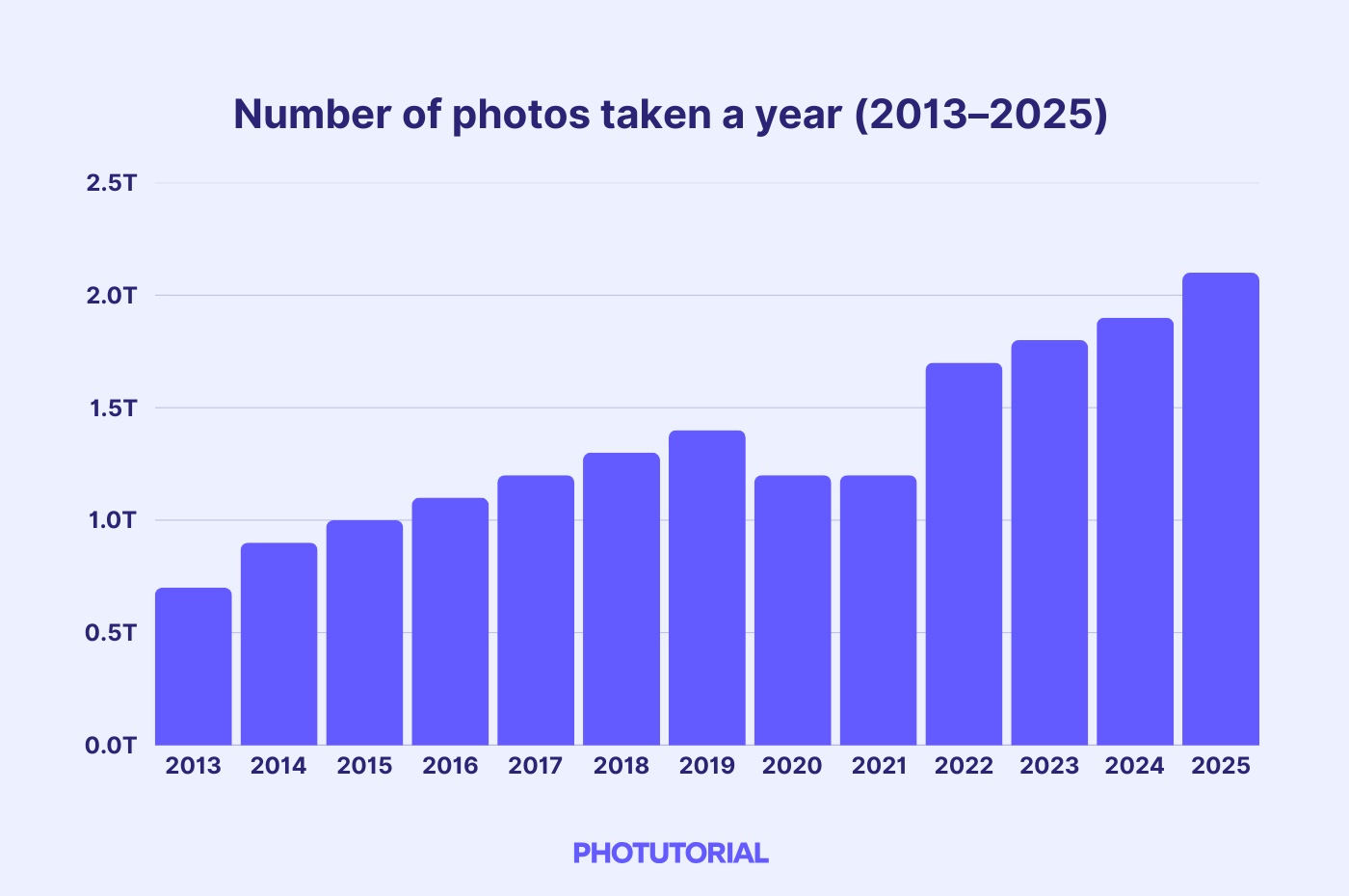

According to Photutorial‘s latest estimates, the 2.1 trillion photo mark (2,100 billion) will be reached in 2025, compared with 1.94 trillion in 2024 and 1.81 trillion in 2023. This rate of growth(around +6 to 8% per year) seems stable since the post-Covid upturn in 2022.

Reducing this quantity to more accessible time scales represents :

- 61,400 photos taken every second,

- 3.7 million per minute, or

- 221 million per hour.

By way of analogy, we would need to photograph every second for 61,000 years to achieve the volume of images produced this year.

Smartphones ultra-dominant, cameras marginalized

According to this study, in 2024, smartphones will account for 94% of all photography worldwide, compared with 4.7% for traditional digital cameras (compact, SLR, hybrid, etc.). The gap is so wide that it is revolutionizing the entire photographic production chain: sensor design, distribution methods, retouching and archiving.

In fact, the pace of change has been rapid: in 2020, 89% of photos were already taken on mobile phones, but this share has continued to rise, making the use of a “traditional” camera residual outside of professional or enthusiast photographers.

Who takes these photos, and where?

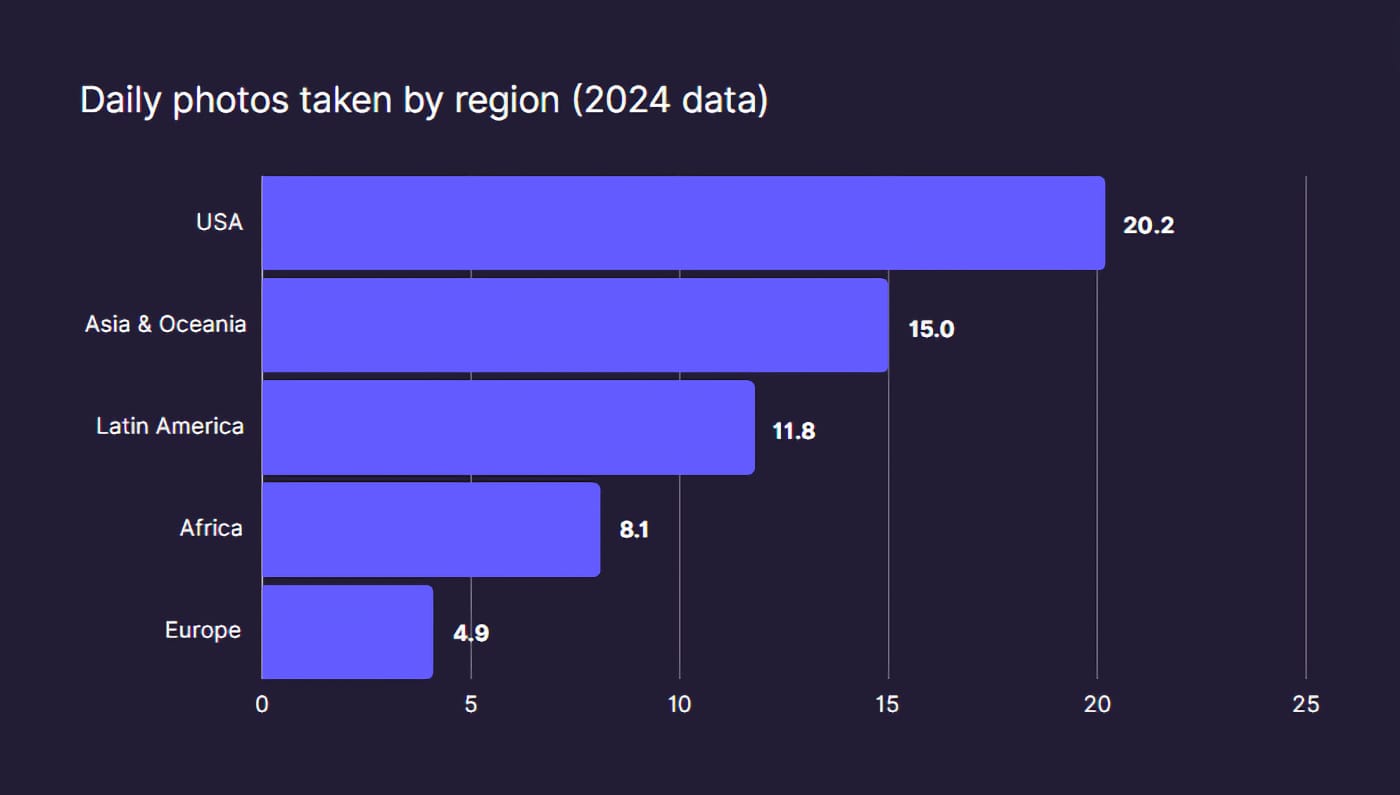

Usage varies widely around the world, with the United States leading the way: the average American takes 20.2 photos a day, well ahead of other geographic regions.

In Asia-Pacific, the average is 15 photos/day, confirming the cultural and social importance of images in this widely connected region. Next come Latin America(11.8 photos/day) and Africa(8.1), while Europe closes the gap with just 4.9 photos/day.

These averages do not reflect the entire population, but rather active users, i.e. those who regularly take photos.

These differences can be explained by a number of factors: equipment levels, access to smartphones or networks, sharing habits, and the value placed on images in public and private spaces.

North America and Asia-Pacific are the biggest producers of images, both in terms of volume and frequency. Conversely, Europe and Africa – for economic, technical or cultural reasons – appear to be areas where the photographic act remains less daily, despite a growing presence on social networks.

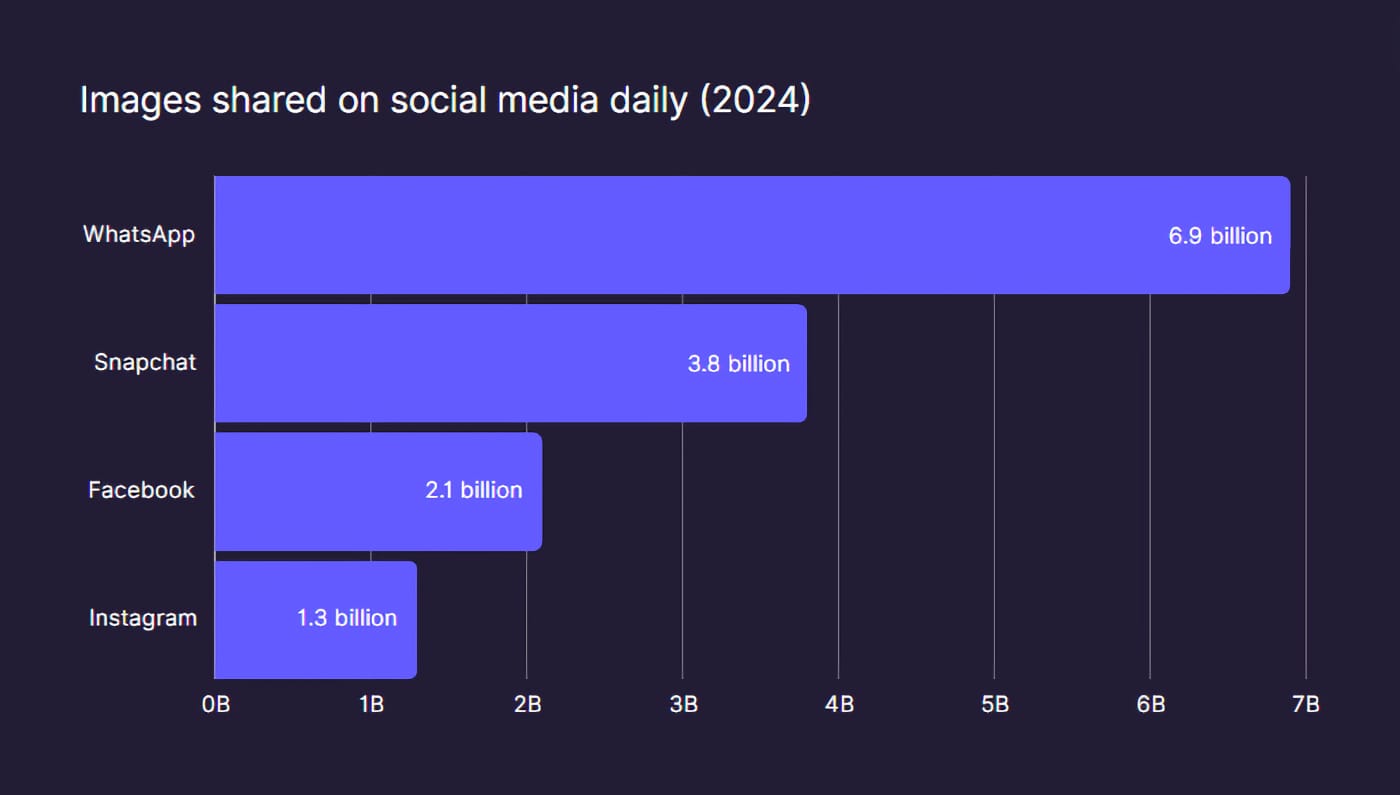

Social networks have become the world’s main means of disseminating images. Every day, some 14 billion photos are shared, a figure that far exceeds the number of snapshots captured daily, as the same image can be disseminated several times: shared, reposted, transformed into a meme.

WhatsApp largely dominates this landscape with 6.9 billion images shared per day, followed by Snapchat(3.8 billion), Facebook(2.1 billion), and Instagram(1.3 billion). Conversely, long-standing platforms such as Flickr record just one million daily shares, a sign of their declining influence, at least in terms of volume.

This visual flow is also fueled by the massive practice of the selfie. In 2024, 94% of photos are taken with a smartphone, and Android devices alone produce 93 million selfies a day. Among 18-24 year-olds, selfies account for around a third of all images captured.

These data confirm the central role played by younger generations in the creation and distribution of personal images, encouraged by optimized mobile interfaces and a culture of instant sharing. The selfie is no longer the exception, but the photographic norm, shaped by technology and social usage.

A colossal (but invisible) visual heritage: 30 trillion images by 2030

As history’s first photograph approaches its 200th anniversary, an estimated 14.3 trillion photos will have been produced by 2024, a volume unimaginable just a few decades ago.

This figure is growing exponentially, with almost 2 trillion new images produced every year. If this trend continues, the total could reach 30 trillion by 2030, or even more if we include visuals generated by artificial intelligence.

Several factors explain this inflation. Firstly, the democratization of mobile photography has put a camera in the hands of billions of people. Secondly, storage capacities have increased, enabling thousands of images to be stored on each phone. Finally, sharing via social networks or messaging systems has led to massive duplication of files. This gigantic corpus of images is a contemporary mirror, both intimate and global, revealing the lifestyles, cultures and concerns of our times.

At the same time, Google Images will only index 136 billion images in 2024. This figure is still low in relation to the global stock of images, underlining the paradox of a digital memory that is dispersed, private and often little consulted.

Methodology and reliability: an aggregate of cross-referenced sources

For this study, author Matic Broz compiles data from secondary sources (Google, Gigaom, industry studies) and extrapolates from confirmed figures (sharing volumes, stock of photos in phones, declared usage). The methodology is based on a combination of surveys, industry reports and Photutorial’s own internal estimates. All updated to May 2025.

It should be noted that the figures shared do not come from public statistical institutes, but from digital platforms or sector-specific research firms. Nevertheless, the internal consistency of the data and the transparency of the sources cited make this a valuable document.

The study is thus positioned as an up-to-date and coherent summary of the state of world photography, while acknowledging the inherent limitations of certain indicators, in particular those linked to digital uses that are difficult to measure precisely.

Conclusion

It’s nothing new: we’ve entered an era of visual overdocumentation. Driven by the democratization of the smartphone, photography has become an everyday gesture, constituting a visual heritage unprecedented in human history. Social networks and messaging applications amplify this phenomenon, encouraging the circulation and duplication of images on an unprecedented scale.

This dynamic poses new challenges in terms of storing, managing and making the most of this mass of images, but it also offers a unique insight into our societies, our cultures and our relationship with images.