ChatGPT‘s recent feature to generate images in the style of the famous Japanese animation studio Studio Ghibli has sparked a heated debate on copyright andartificial intelligence. This trend, which has rapidly gained momentum on social networks, raises complex questions about the boundary between inspiration and intellectual property infringement.

Sommaire

On March 26, 2025, OpenAI unveiled its new GPT-4o image generation model. This version breaks away from DALL-E, allowing images to be created directly in ChatGPT. Featuring advanced reasoning capabilities, it allows users tointeract with the image through a series of prompts. The aim is to facilitate successive iterations to generate ultra-realistic images, with particular attention paid to text rendering.

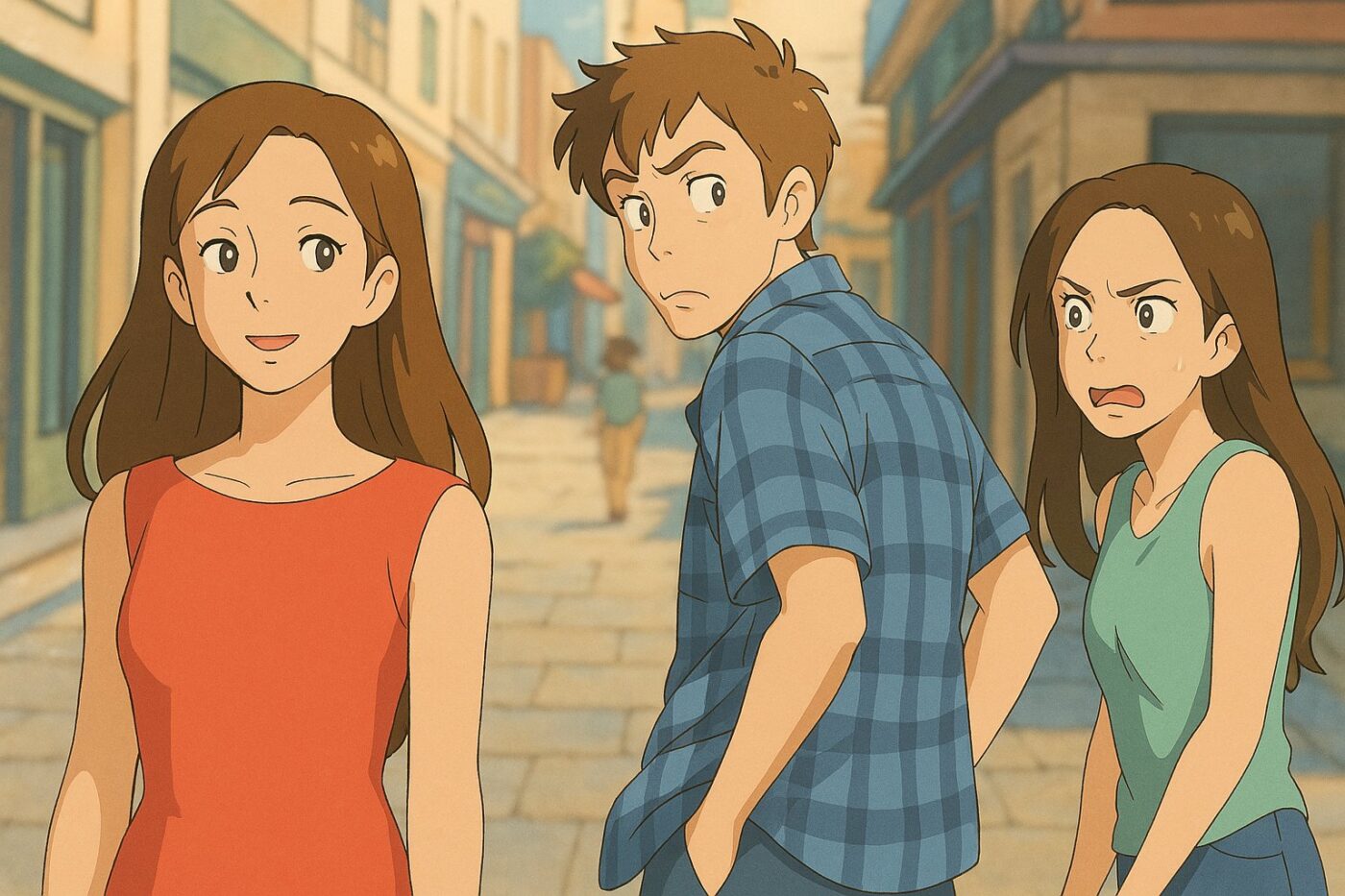

But this new version was mainly used to create images inspired by Hayao Miyazaki films such as Castle in the Sky, My Neighbor Totoro and Chihiro’s Journey. And that’s all it took for many people to share their creations on X (formerly Twitter) and for it to become a major Internet trend.

These illustrations are characterized by pastel tones, expressive-looking characters and subdued lighting – an enchanting atmosphere that perfectly mirrors the world of the Japanese master.

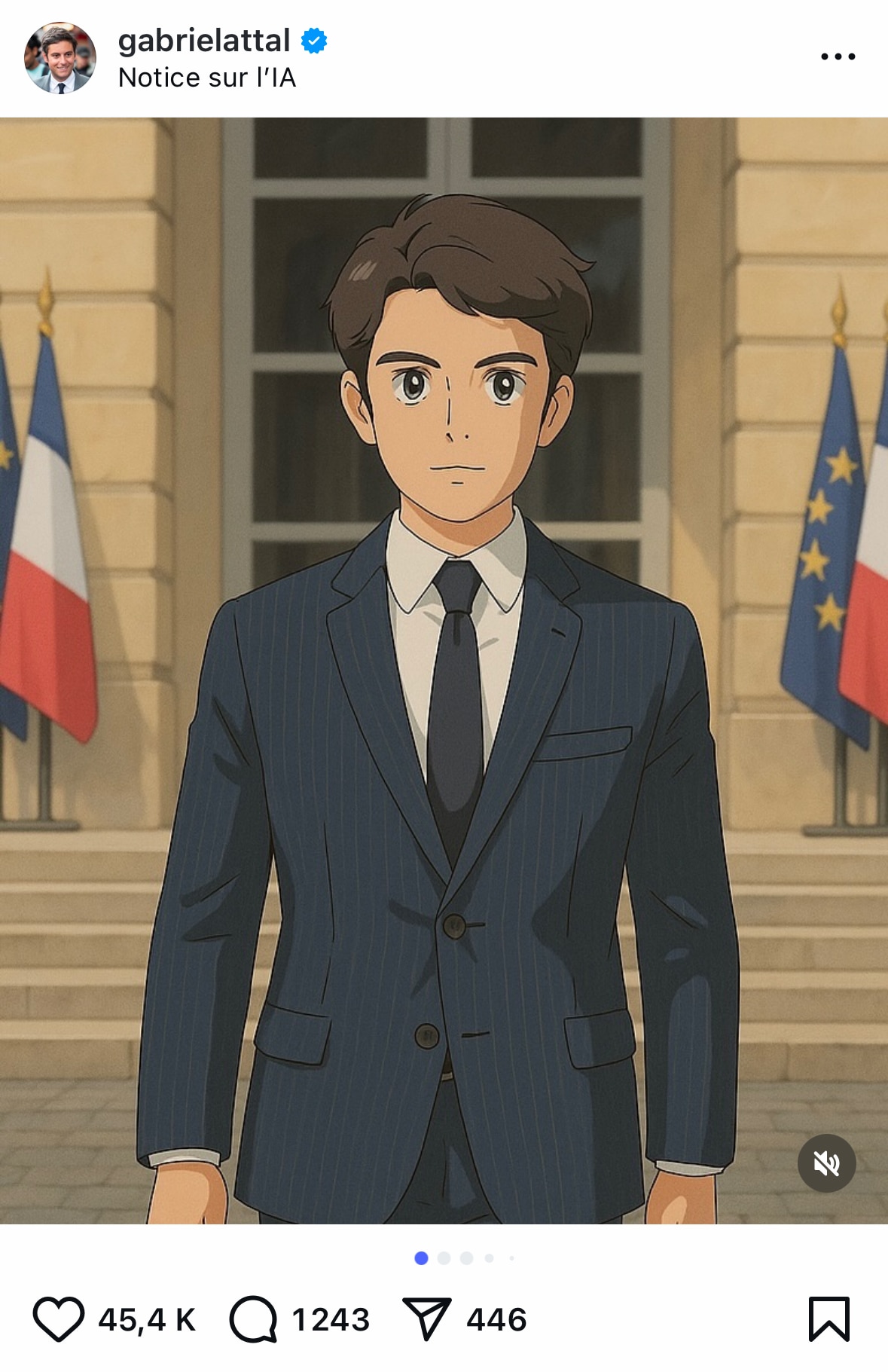

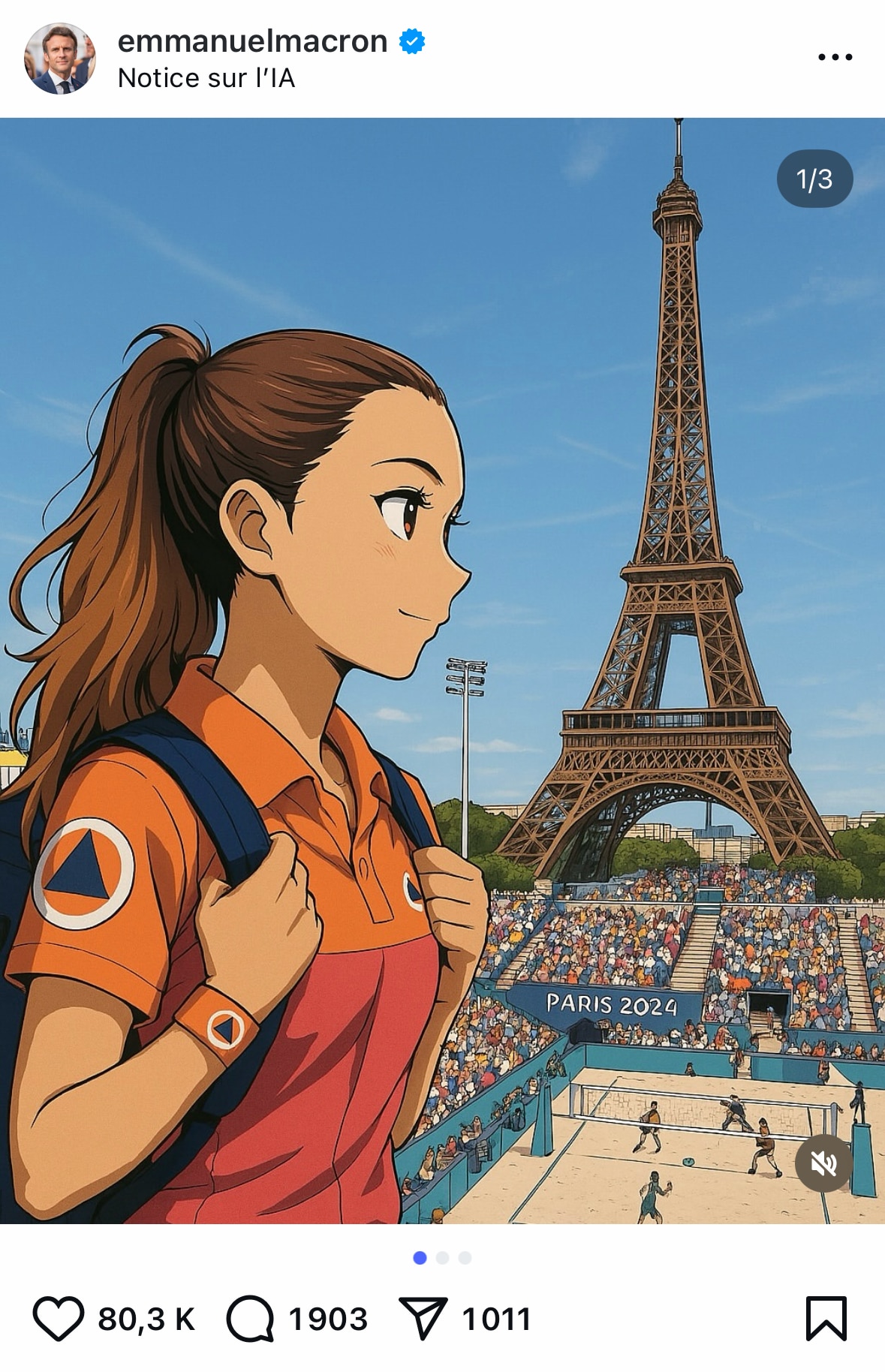

They invaded personal accounts on X, but also those of public figures such as Emmanuel Macron. However, this success quickly outstripped the technical capabilities of OpenAI, which had to restrict access to this option to avoid overloading its servers. Sam Altman, shared a humorous message on X: “Can you please calm down by generating images. Our team needs sleep”.

On April 1, 2025, OpenAI reopened access to the tool to all ChatGPT accounts, including free accounts.

Complex legal issues

Could this be a successful advertising campaign for an upcoming Studio Ghibli film? No, because OpenAI did not obtain any license to generate these images inspired by the works of the Japanese animation studio.

The style of an image is certainly not protected by copyright, unlike specific works (films, characters, precise settings, etc.). This nuance would allow OpenAI to let anyone transform a snapshot into a Studio Ghibli-inspired image, as long as it doesn’t involve reproducing the original characters.

However, the real challenge lies elsewhere: to create these on-demand images, OpenAI had to train its AI models on specific copyrighted works by Studio Ghibli. And for this, OpenAI did not obtain a license.

Is training an AI on protected content an infringement?

According to Joëlle Verbrugge, a photographer and lawyer specializing in photography law, “the mere fact of having integrated the original works into the AI’s training base could possibly be considered an infringement in itself “. This issue is at the heart of a chapter in her book AI et image : guide juridique. The author notes that recent case law is divided, with some decisions condemning AI companies, others not.

It is also believed that Studio Ghibli could take legal action, but this would require proof thatOpenAI’s models had been trained directly on the studio’s works.

OpenAI defends itself by invoking “fair use”, a doctrine recognized in the USA, which allows the use of copyright-protected content without authorization under certain specific conditions. The aim is to encourage creation, innovation and the dissemination of knowledge.

OpenAI also claims that its aim is to give users “the greatest possible creative freedom.”

An economic impact for Studio Ghibli?

For Joëlle Verbrugge, Studio Ghibli could also accuse OpenAI of“economic parasitism“, by accusing companies exploiting AI of profiting from the notoriety of their creations. According to Studio Ghibli, this approach is the most likely to win their case. On the other hand, if everyone can generate images in the spirit of Studio Ghibli, this could be economically damaging to the company.

For his part, Hayao Miyazaki, the father of Studio Ghibli, has not commented on the controversy, even though he announced 9 years ago on the subject of AI:“I’m deeply disgusted. If you really want to do these appalling things, go ahead. But I have no desire to integrate this technology into my work. I feel deeply that it’s an insult to life itself.”

Further information: AI and image: a legal guide